Could there be a symbol more ironic than the cross? The instrument of the most terrifying, arguably worst-possible death, has become the world’s most beloved symbol of eternal life. The cross is so candy-coated, so bathed in sugar and sweetness, it is impossible to grasp the bitter horror it once created. Consider the words of one of ancient Rome’s greats, Cicero:

Cicero described crucifixion as “a most cruel and disgusting punishment,” arguing “the very mention of the cross should be far removed not only from a Roman citizen’s body, but from his mind, his eyes, his ears … It is a crime to bind a Roman citizen, to scourge him a wickedness, to put him to death is almost parricide. What shall I say of crucifying him? So guilty an action cannot by any possibility be adequately expressed by any name bad enough for it.”

Cicero–one of history’s greatest orators–can find no words to convey the evils of crucifixion. Yet we hang crosses around our necks, on our walls, and above our baby’s cribs. We must re-capture some sense of the horror.

Crucifixion was invented and perfected by Persians, Carthaginians, even Greeks. The cruelty of the ancient world knew no bounds–and it only got worse:

The Roman Empire did for crucifixions what the assembly line did for manufacturing: suddenly crosses were everywhere.

But how familiar were the people of Israel with death by crucifixion? Quite familiar, as it turns out.

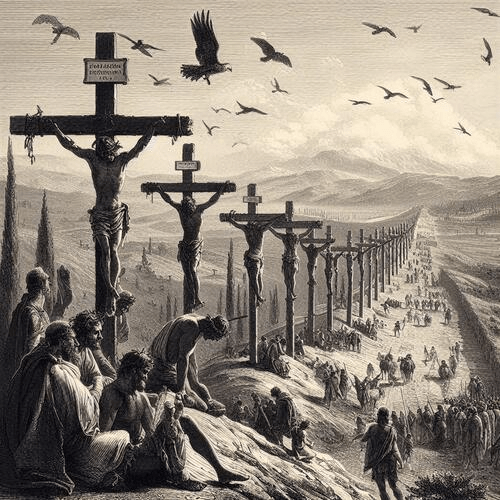

Some 70 years before the birth of Christ, a gladiator named Spartacus led a rebellion against Rome employing escaped slaves as soldiers. Spartacus and his men were defeated and captured. Then, in order to set a public example, the 6,000 who had escaped slavery were crucified along the Appian Way, one of history’s first superhighways. The men were crucified at 60-yard intervals, so that the 6,000 crosses on which men were bleeding and dying (and left to rot) would stretch 100 miles from Rome to Capua. A second group of slaves were believed to have been crucified along the Via Latina, another road leading from Rome to Capua.

Can you imagine 6,000 crucifixions happening simultaneously?

Everyone would hear about it. Rome used the horrible method of capital punishment to strike terror into the hearts of political rivals, rebels, traitors, and pirates of every sort. Where today’s dictators destroy their enemies with gas chambers, firing squads, even forced starvation, Romans preferred stripping troublemakers naked and nailing them to stakes. Then they were left hanging in the sun until they died of dehydration and exposure, a process that could take days. Meanwhile, the public was paraded in front of them, sometimes for amusement, but often as a warning.

When 6,000 slaves were crucified along the Appian Way, slave owners brought their slaves out for a field trip: this is what can happen to you if you try to escape.

Death by the cross may have been history’s most brutal form of capital punishment, designed to maintain the status quo and suppress dissent. It was an atrocity committed by a government with no regard for human life much less human rights (a novel concept at the time). The cross was meant to strike terror in the hearts of would-be rebels, and was considered so deeply humiliating it was illegal to crucify a Roman citizen.

Crucifixion was not unfamiliar to the people of Israel. When Jesus spoke of it, His audience knew exactly what He was talking about.

Only four years before the birth of Christ, the Roman General Varus crucified 2,000 Jews.

The year 70 AD saw thousands of crucifixions in Jerusalem. When Titus laid siege to Jerusalem in 70 AD, Roman troops crucified as many as 500 Jews a day—FOR SEVERAL MONTHS. (If they crucified only 100 a day for three months, that would mean the Romans crucified a minimum of 9,000 Jews.)

Everyone in Israel would have heard about crucifixions. They saw the brutality of Rome. They had seen the ruthless ways of her godless, merciless soldiers. These men would not hesitate to pound nails into you and hang you up to die. It was amusing to them, an entertaining mockery of another unlucky loser. You could not hope for mercy from the Romans. If the cross was your sentence it meant the slowest, most painful, terrifying, humiliating death possible. Anyone who had seen it would be horrified by it.

Against this background of terrifying, humiliating, de-humanizing crucifixions, what does Jesus say to His followers—not only to those listening, but to you and me?

“If you don’t pick up your own cross and come after Me, you cannot be My disciple” Luke 14:27.

What? Pick up a cross?

After His death and resurrection, everyone knew Jesus had carried His own cross. And years before His death (knowing what was coming), He said if we don’t take up a cross of our own, we cannot be His disciple.

What does that mean? Following Constantine’s elimination of crucifixions as a form of capital punishment, few alive today have even seen a cross, much less picked one up. Jesus is not speaking of a literal cross.

Consider the context. Jesus says “if you do not hate your father, mother, wife, and children, brothers and sisters—yes, and even your own LIFE, you cannot be My disciple” Luke 14:26. In other words, you should love nothing as much as you love Jesus. Your love for your family, your spouse, even your children should not compete with your love for Jesus. In fact, you should love Jesus more than you love your own life. (Are you ready to die for Him?)

But isn’t all of this just poetry? Surely He can’t be serious?

On the contrary, how much more serious could He be? What is more serious than the worst possible death mankind could ever devise? This is not mere poetry. This is serious. You must love Jesus more than everything, every ONE, and even more than yourself or your own life. Do you love Him more than your hopes and dreams? More than your most cherished goals? Jesus commands you to love Him more than everything on your resume and everything on your bucket list. Nail both documents to the cross and let them go. And love Him more than all your loved ones.

“If anyone comes to Me and does not hate his own father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters—yes, and even his own life—he cannot be My disciple.”

Dear Lord, we give you all our loves, our goals, our most cherished people and our most cherished wishes. We give them all to you. Help us love you more than everything else. Thank you for enduring the incredible cross for us. Help us love you the same way.

Read Luke 14.

ΑΩ