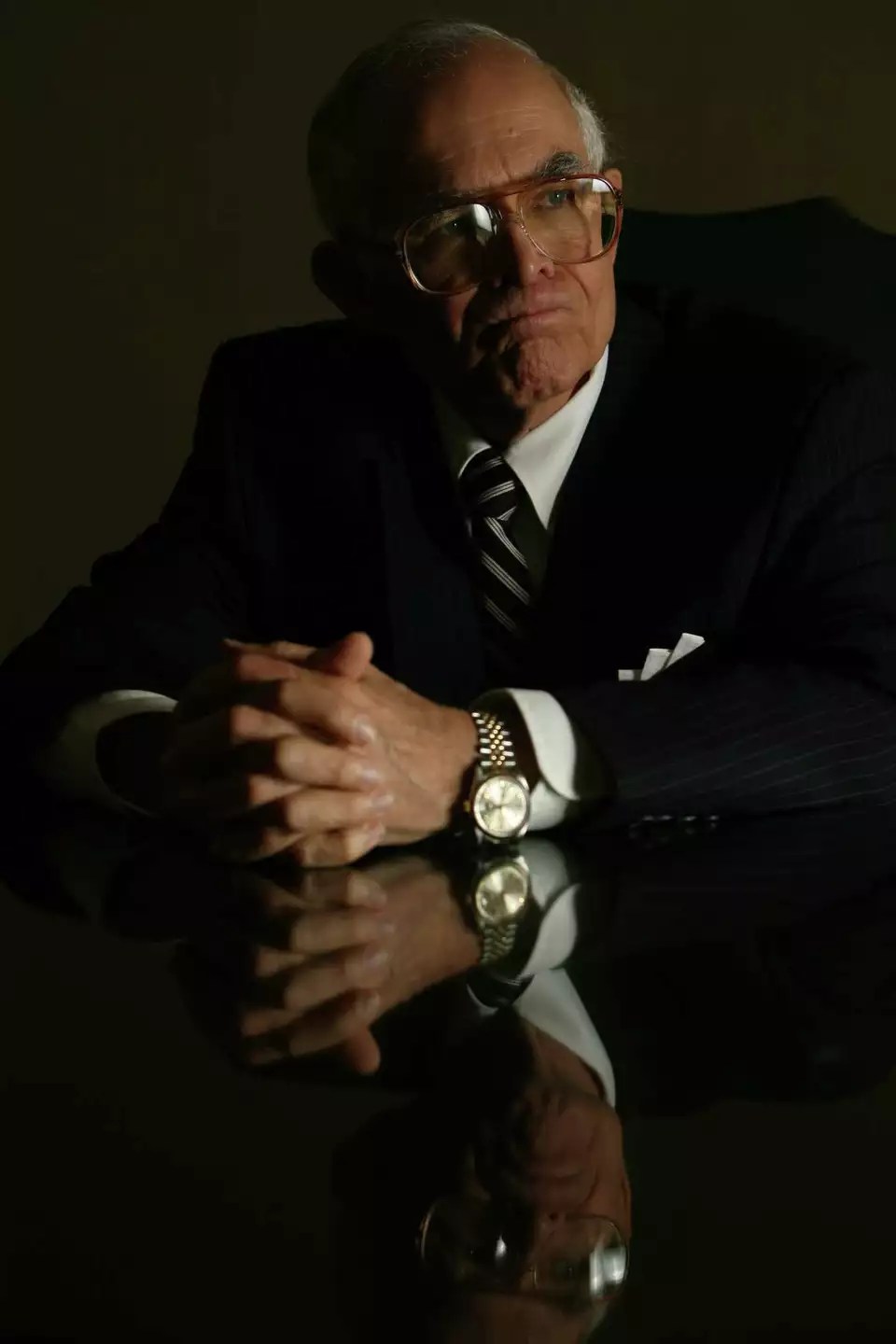

The company I work for was started by Joe D. some 75 years ago. By the time I was hired, the baton had been passed to Joe’s son, Jim D. Jim was a slight, white-haired man. He was extremely nice, a great storyteller, and a talented networker. Mr. D. had powerful friends all over Texas. He was a gifted rainmaker, regularly bringing in millions of dollars in new business. When Jim retired, the partners voted to sell the civil engineering firm to a national company.

Now that the dust has settled, daily life under the new regime is not that different. But I receive a lot more email, sometimes a dozen messages a day from Pennsylvania and other places, most of which I skim at best. But once a week I get an email from the president of the new company, or as I think of him, the new Jim D.

His name is Mike. Mike is much younger, taller, and balder than Jim, but seemed friendly enough the one time I met him. I try to read Mike’s emails. I am not interested in the constant updates from I.T., H.R., and the “Ladies Who Lunch.” But something about President Mike does capture my attention. Because he is the man, you know what I mean?

A risk facing any growing organization, whether school, church, business, or nation, is the decentralization and diffusion of leadership. The larger an organization grows[1], the more it needs a strong, individual leader who can cast a vision for the organization and channel the energy and creativity of the people toward a few key goals[2].

When Moses died, Joshua became the new leader. Under Joshua’s leadership, Israel moved into the Promised Land, fought many battles, and established its claim to a great deal of territory. But when Joshua died, Israel did not appoint a new executive. Instead, authority was decentralized and tribal leaders ruled the nation. There was no king, no President Mike, and not even a judge.

Left to themselves, the tribal leaders were not that successful.

“Judah could not drive out the inhabitants of the valley … The children of Benjamin did not drive out the Jebusites … Neither did Manasseh drive out the inhabitants of Beth-Shean … Neither did Ephraim drive out the Canaanites … Neither did Zebulun drive out the inhabitants of Kitron … Neither did Asher drive out the inhabitants of Accho … Neither did Naphtali drive out the inhabitants of Beth-Shemesh … And the Amorites forced the children of Dan into the mountains, for they would not allow them to come down into the valley” Judges 1:19-34.

There may be several reasons the tribes struggled to free themselves of the Canaanites. But one of those reasons is surely the lack of focused, executive leadership. There was no Moses. There was no Joshua. There was certainly no King David. There was not even a judge like Samson or a prophet like Samuel.

Instead, “after Joshua’s death, power and authority were decentralized to the tribal leaders, and the tribes were no longer unified in purpose.”[3]

There was no President Mike sending weekly emails.

There was no Pastor Gregg preaching 30 minutes a week from a single location but being “livestreamed” to three other locations.

The 12 tribes were on their own. What happened? They fell into sin and idol worship, “whoring after other gods,” (Judges 2:17), and were soon captured by Aram, King of Mesopotamia.

These people who had finally—FINALLY—gotten into the Promised Land were forced to stop working on their own houses and farms and had to serve one of the evil kings they had failed to defeat.

But God was merciful and after eight years, raised up Othniel, brother of Caleb, to deliver Israel and serve as its first judge, Judges 3:7-11.

And who were these Old Testament judges? Did they wear black robes and adjudicate cases, rapping on the bench with an oaken gavel, a mahogany mallet? No. The judges decided cases, of course. But these were not judges as we use the term today.

The Old Testament judges were executives.

Each Old Testament judge was a single, national leader. The judges were often military leaders and battlefield strategists. But they were also national figures, celebrated leaders of a sort that could cast a vision for the nation, give the people wisdom and goals for the days ahead, encourage them in hard times, and congratulate them in good times.

The Book of Judges is really a book of Executives.

We need to appreciate our leaders. They carry heavy burdens.

Today a line from Shakespeare is paraphrased: “Heavy is the head that wears the crown.” So true.

One of the crowns King Charles wears weighs over four pounds. That must get heavy after a while. But of course, we are speaking metaphorically. Being king is a heavy responsibility. So is president. Or CEO. Or principal. Or head coach. Or pastor.

I once spent about two years working as a church youth director. The work was hard enough. But the burden I felt for the souls of those students was so much greater than the nine-to-five work. Pray for your pastors!

Dear God, give us great, gifted, wise, humble leaders. Bless our churches with men who put God first and their family second. Bless us with wise leadership. Bless us with praying leadership. In this new day of multi-site churches, raise up gifted preachers, and especially raise up humble men of God who are content to play a vital supporting role. Bless us with bold but humble leaders. Make us grateful for each of them—and help us to show it!

AΩ.

[1] A related risk is the Pareto Principle. The Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, states that in many situations, 80% of the results are generated by only 20% of the causes. As most understand it, the Pareto Principle says that eighty percent of sales are generated by twenty percent of customers, or eighty percent of job tasks are accomplished by twenty percent of the employees.

But looking more closely into the mathematics, Jordan Peterson (former Harvard professor and well-dressed internet personality) explains that for a growing enterprise, the Pareto Principle may be more devastating than it sounds. “The actual [Pareto Principle] is, the square root of the number of people involved in an enterprise do half the work. If you have ten people who work for you, three of them do half the work. Now that seems understandable, right? But if you have a hundred, ten of them do half the work. And if you have 10,000 employees, a hundred of them do half the work. So what that means is that as your enterprise grows, the number of people who are engaging in counterproductive activity scales much faster than the number of people who are being productive.”

In other words, the Pareto Principle indicates that the larger an institution becomes the more its people are drawn off-task, losing sight of institutional goals.

[2] Consider the United States. When the thirteen colonies won independence from England, many wanted to operate as a loose confederacy of nation-states, linked only by a weak central government. But it soon became clear that if this nation were to survive, it would require a strong federal government. I say this as a tenth-amendment advocate: we cannot ignore states’ rights. But the federal government will always have superseding authority.

[3] Chronological Life Application Study Bible, Tyndale House, Carol Stream, 2004, p366, note on Judges 1:21.